It all started with ... (My Catalogue Notes)

Fong So

*The text uploaded here is extracted from an origninal text of about 5,500 words published in September 2011 in a catalogue to accompany the exhibition entitled The Centenary of China's 1911 Revolution: Paintings and woodcut prints by Fong So.

It is generally agreed that modern China began with the 1911 Revolution (the Xinhai Revolution). A large number of books, scholarly works and general reading materials about the Revolution are available. Nearly all of them start with the story of Sun Yat-sen, the most influential revolutionary of the time.

The life story of a man can be told in many ways. Sun Yat-sen himself told his own life story many times during his life time. In 1923, two years before his death, while giving a speech at the University of Hong Kong, he began his life story with his school years in Hong Kong. Some twenty-seven years before that, in 1896, when he was still a young revolutionary in exile, he told his life story in his first autobiography beginning with what he called the 'late age'.

I didn't think that much about the beginning and the end, when I embarked on this paintings and woodcuts project. From the start I believed there would be some way to present the artworks when they were finished. Then the order given to the series of artworks would tell the beginning through to the end. The project started early last year, with the first piece of artwork appearing in June 2010 and the last piece being finished as late as July 2011. When I started to produce this catalogue, I came to the conclusion that the easiest and most natural way to arrange the whole series was to follow a chronological order. Therefore, my Xinhai project exhibition starts with the 'late age' of Sun Yat-sen and his contemporaries.

In 1896, when Sun Yat-sen was a fugitive sojourning in England., he was introduced to a Cambridge sinologist, Professor H.A. Giles, by Dr James Cantlie, his teacher at the School of Medicine in Hong Kong. At that time Sun had just became a celebrated anti-Qing revolutionary after being kidnapped by Qing officials at the China Legation in London and then freed. He was invited by Professor Giles to write an autobiography to be included in his work A Chinese Biographical Dictionary. He obliged by writing Giles a letter, in which he wrote that he was “born in a late age”. For me, the best way to visualize Sun's 'late age'‚ is to produce an image of what people and life looked like at that time. To do this, I drew inspiration from an old Hong Kong picture of the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), which records the scene of a crowd watching an open-air theatre production. Hong Kong at that time, ceded in 1842 after the First Opium War, was a colony under British rule. I first saw the picture in an old album published in 1970 by the then City Museum and Art Gallery of Hong Kong. In my composition, I cut out the background, focusing on the heads of the crowd and people's facial expressions. The background is replaced by an excerpt from Sun's letter to Giles. It is more than an excerpt: it follows the calligraphy of Sun's letter. Before working on this piece, I had tried to avoid putting inscriptions into my paintings, though it is a common practice for nearly all painters using the Chinese media of brush and ink. I modified their practice by using diluted or 'watered down' ink to copy Sun's calligraphy. That way, it is in 'Sun-style' and I am just a 'copycat'. The portrait of the young Sun Yat-sen is next to those words composed by him (Plate no. 1).

......

Very little visual material is left from the 1911 Wuchang uprising. We know that it was the rising in revolt of the Qing New Army soldiers that fired the first shot of the revolution. Old pictures now available are mostly those poorly-equipped New Army soldiers. We also know that an 18-star red flag, symbolizing the unification of China's 18 provinces at that time, was used by the insurrection army. As the Hubei Viceroy's Yamen, the Qing government's headquarters in the province, was destroyed by artillery fire in the uprising; the newly-founded Hubei Military Government turned the building that housed the provincial assembly into its headquarters. Here, in my attempt to visualize the 1911 Revolution, I have combined the insurrection soldiers, the 18-star red flag and the insurgents' headquarters, known among the locals as the Red Mansion, with Sun Yat-sen's remarks about this uprising (No. 12). According to Sun, the success in Wuchang came as an 'accident'.......

Sun Yat-sen was on a tour in the United States of America when the Wuchang uprising broke out. While stopping over at Denver, Colorado, he read in a newspaper that the move in Wuchang turned out to be a success. He continued his tour to New York, then Britain and France, before returning to China. Shortly after his arrival, he was elected the Provisional President of the Republic by the provincial delegates. On 1 January 1912, he went to Nanking to assume the post and inaugurate Year One of the newly founded Republic of China. The oath he took, a piece of his calligraphy, can be found reproduced in various publications. In the portrait I did of Sun, I have his oath copied next to him (No. 14).

......

The Provisional Governemnt in Nanking (Nanjing) operated for just three months, from 1 January to 31 March 1912. After the abdication of the young Manchu Emperor Xuantong, an official ceremony was held in Nanking in which Sun Yat-sen, the Provisional President, led the officials of his Provisional Government to the Ming Mausoleum to pay homage to the founder of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the dynasty before the Qing. My composition of the Provisional Government is based on the old pictures left from that special occasion. In this composition (No. 16), Sun is in the middle of the front row; at his side is Huang Xing, the Minister of the Army. Some other ministers of Sun's cabinet are there, but there is no need to name them one by one. The three big characters carved on the gate of the Ming tomb, as well as the titles of the Provisional Government's gazette and the Provisional Constitution, form the backdrop. Also in display is the five-colour national flag used by the newly-founded Republic. The flag continued to be in use until 1928.

......

Revisiting Hong Kong, Sun Yat-sen gave a speech at the University of Hong Kong on 20 February1923. He told his audience that Hong Kong was his intellectual birth-place and the place where he got his revolutionary and modern ideas. A good pictorial record of the occasion is a photograph taken outside the Great Hall (now Loke Yew Hall) after Sun's speech. This is the photograph on which my largest-ever woodcut is based (No. 21). In this particular piece, I focused on the section in the middle; only those around Sun were included (my apologies to those cropped out). I added only one thing not seen in the photograph: the clock tower above the Great Hall.

......

According to my parents, they had to recite the testament of the Founding Father of the Country (Sun Yat-sen) at school during their school years. That was some seventy years ago. The testament is copied in my work “The Last Wishes” (No. 23), but not in full. It is in 'Wang-style' calligraphy, as the testament was drawn up by Wang Jingwei at Sun's dictation or composed by Wang with Sun's approval. Wang was then a high-ranking Kuomintang leader among Sun's entourage and was one of the very few non-family members who were allowed to be there by Sun's sickbed.

......

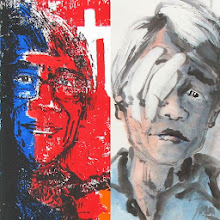

The next piece “The Prolonged Enmity” (No. 26) is a pictorial summary of a long history. Featuring Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, I summarized the hostilities between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in a single piece. On the left side, Mao is shown in three stages: first as a 'red bandit' in his Jiangxi period (the early 1930s); then as the communist leader winning the civil war (1946-49); and lastly as the great leader of the CCP and the country until his death (1949-76). On the right side, Chiang is also shown in three stages: first at Sun Yat-sen's side commanding the KMT army; then as the 'Generalissimo' of the country during the war against Japanese invasion (1937-45); and lastly as head of the KMT government ruling Taiwan (1949-1975).

......

Two woodcuts are made to wrap up this centenary series: “Waiting” (No. 34) and “The Arab Spring” (No. 35). As things and events related to these two pieces are so fresh, there is no need to explain everything in detail.All inscriptions are of remarkable origins. I hope they can stimulate thought and contemplation. After working on these pieces, I became fond of Solveig's Song and jasmine.

There are some short stories I should like to recount before ending my catalogue notes

Over the past year, while I have been working on this project, a question has been frequently put to me. The question is: “How did the project come about?” The answer is: “It all started with a casual chat some time early last year (2010) among friends, most of them old acquaintances going back to my university years.” Over tea or wine, one of them exclaimed: “Now that it's the year 2010, the next will be 2011. A hundred years have gone by and things are still like this!” There was no need for further explanation; we all knew what he meant to say. The casual talk then turned into a preliminary exchange of ideas about my plan to produce a painting and woodcut series to mark the centenary of the Xinhai Revolution. Some of the friends joining the casual talk later became the members of my Xinhai task group.

The conclusion of our casual talk on that day was a straightfoward one, as offered by one of the participants citing the words of Sun Yat-sen: “The revolution has not been successfully concluded yet; comrades should strive on!” I later carved a seal based on this well-known saying by Sun, but leaving out the words “revolution” and “comrades”. The seal print now appears in some of the brush-and-ink paintings in this centenary series.

Another short story is my fond memory of my old mentor when I was a small boy living in Gaungzhou. His name is He Xia. I met him by chance at the age of ten, while I was making a sketch of a painting in an art gallery. He was then a retired old man of about seventy. He introduced me to the art of the Lingnan masters, in particular that of the founder of the School, Gao Jianfu. He later introduced me to another Lingnan master, Professor Chao Shao-ang, who would became my painting teacher when I moved to Hong Kong. Professor Chao had been the student of Gao Jianfu's younger brother Gao Qifeng, another famous Lingnan master. I know very little about my old mentor He Xia, except that he had been a soldier working at the side of Sun Yat-sen when he was young. He did not paint; he practiced calligraphy. He showed me his collection of calligraphy and paintings. I remember that a piece of calligraphy hanging in his study was penned by Sun Yat-sen. Some time last year, while digging out some old stuff in my studio, I found by chance that I still kept a letter written to me by my old mentor some 45 years ago. It was years after I moved to Hong Kong that I came to know the extraordinary life story of Gao Jianfu (1879-1951). He happened to be a member of the Revolutionary Alliance when he stayed in Japan in 1906. In the 1911 Canton (Guangzhou) uprising in April, he was one of the team leaders of the enlisted revolutionary fighters. He took refuge in Hong Kong after that failed attempt and continued to be an activist. After the Xinhai Revolution, he became a modern master promoting the 'New Chinese Painting Movement' and founded the Lingnan School. I very much share his guiding principle of 'New Chinese Painting': “brush and ink should follow [the development of] time.”

(Contents of the exhibition catalogue include: colour plates of all 35 artworks; chronology; an essay by Louie Kin-sheun; biographical sketches of over 50 historical figures; Fong So's catalogue notes and selected bibliogrphy.)

The life story of a man can be told in many ways. Sun Yat-sen himself told his own life story many times during his life time. In 1923, two years before his death, while giving a speech at the University of Hong Kong, he began his life story with his school years in Hong Kong. Some twenty-seven years before that, in 1896, when he was still a young revolutionary in exile, he told his life story in his first autobiography beginning with what he called the 'late age'.

I didn't think that much about the beginning and the end, when I embarked on this paintings and woodcuts project. From the start I believed there would be some way to present the artworks when they were finished. Then the order given to the series of artworks would tell the beginning through to the end. The project started early last year, with the first piece of artwork appearing in June 2010 and the last piece being finished as late as July 2011. When I started to produce this catalogue, I came to the conclusion that the easiest and most natural way to arrange the whole series was to follow a chronological order. Therefore, my Xinhai project exhibition starts with the 'late age' of Sun Yat-sen and his contemporaries.

In 1896, when Sun Yat-sen was a fugitive sojourning in England., he was introduced to a Cambridge sinologist, Professor H.A. Giles, by Dr James Cantlie, his teacher at the School of Medicine in Hong Kong. At that time Sun had just became a celebrated anti-Qing revolutionary after being kidnapped by Qing officials at the China Legation in London and then freed. He was invited by Professor Giles to write an autobiography to be included in his work A Chinese Biographical Dictionary. He obliged by writing Giles a letter, in which he wrote that he was “born in a late age”. For me, the best way to visualize Sun's 'late age'‚ is to produce an image of what people and life looked like at that time. To do this, I drew inspiration from an old Hong Kong picture of the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), which records the scene of a crowd watching an open-air theatre production. Hong Kong at that time, ceded in 1842 after the First Opium War, was a colony under British rule. I first saw the picture in an old album published in 1970 by the then City Museum and Art Gallery of Hong Kong. In my composition, I cut out the background, focusing on the heads of the crowd and people's facial expressions. The background is replaced by an excerpt from Sun's letter to Giles. It is more than an excerpt: it follows the calligraphy of Sun's letter. Before working on this piece, I had tried to avoid putting inscriptions into my paintings, though it is a common practice for nearly all painters using the Chinese media of brush and ink. I modified their practice by using diluted or 'watered down' ink to copy Sun's calligraphy. That way, it is in 'Sun-style' and I am just a 'copycat'. The portrait of the young Sun Yat-sen is next to those words composed by him (Plate no. 1).

......

Very little visual material is left from the 1911 Wuchang uprising. We know that it was the rising in revolt of the Qing New Army soldiers that fired the first shot of the revolution. Old pictures now available are mostly those poorly-equipped New Army soldiers. We also know that an 18-star red flag, symbolizing the unification of China's 18 provinces at that time, was used by the insurrection army. As the Hubei Viceroy's Yamen, the Qing government's headquarters in the province, was destroyed by artillery fire in the uprising; the newly-founded Hubei Military Government turned the building that housed the provincial assembly into its headquarters. Here, in my attempt to visualize the 1911 Revolution, I have combined the insurrection soldiers, the 18-star red flag and the insurgents' headquarters, known among the locals as the Red Mansion, with Sun Yat-sen's remarks about this uprising (No. 12). According to Sun, the success in Wuchang came as an 'accident'.......

Sun Yat-sen was on a tour in the United States of America when the Wuchang uprising broke out. While stopping over at Denver, Colorado, he read in a newspaper that the move in Wuchang turned out to be a success. He continued his tour to New York, then Britain and France, before returning to China. Shortly after his arrival, he was elected the Provisional President of the Republic by the provincial delegates. On 1 January 1912, he went to Nanking to assume the post and inaugurate Year One of the newly founded Republic of China. The oath he took, a piece of his calligraphy, can be found reproduced in various publications. In the portrait I did of Sun, I have his oath copied next to him (No. 14).

......

The Provisional Governemnt in Nanking (Nanjing) operated for just three months, from 1 January to 31 March 1912. After the abdication of the young Manchu Emperor Xuantong, an official ceremony was held in Nanking in which Sun Yat-sen, the Provisional President, led the officials of his Provisional Government to the Ming Mausoleum to pay homage to the founder of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the dynasty before the Qing. My composition of the Provisional Government is based on the old pictures left from that special occasion. In this composition (No. 16), Sun is in the middle of the front row; at his side is Huang Xing, the Minister of the Army. Some other ministers of Sun's cabinet are there, but there is no need to name them one by one. The three big characters carved on the gate of the Ming tomb, as well as the titles of the Provisional Government's gazette and the Provisional Constitution, form the backdrop. Also in display is the five-colour national flag used by the newly-founded Republic. The flag continued to be in use until 1928.

......

Revisiting Hong Kong, Sun Yat-sen gave a speech at the University of Hong Kong on 20 February1923. He told his audience that Hong Kong was his intellectual birth-place and the place where he got his revolutionary and modern ideas. A good pictorial record of the occasion is a photograph taken outside the Great Hall (now Loke Yew Hall) after Sun's speech. This is the photograph on which my largest-ever woodcut is based (No. 21). In this particular piece, I focused on the section in the middle; only those around Sun were included (my apologies to those cropped out). I added only one thing not seen in the photograph: the clock tower above the Great Hall.

......

According to my parents, they had to recite the testament of the Founding Father of the Country (Sun Yat-sen) at school during their school years. That was some seventy years ago. The testament is copied in my work “The Last Wishes” (No. 23), but not in full. It is in 'Wang-style' calligraphy, as the testament was drawn up by Wang Jingwei at Sun's dictation or composed by Wang with Sun's approval. Wang was then a high-ranking Kuomintang leader among Sun's entourage and was one of the very few non-family members who were allowed to be there by Sun's sickbed.

......

The next piece “The Prolonged Enmity” (No. 26) is a pictorial summary of a long history. Featuring Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, I summarized the hostilities between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in a single piece. On the left side, Mao is shown in three stages: first as a 'red bandit' in his Jiangxi period (the early 1930s); then as the communist leader winning the civil war (1946-49); and lastly as the great leader of the CCP and the country until his death (1949-76). On the right side, Chiang is also shown in three stages: first at Sun Yat-sen's side commanding the KMT army; then as the 'Generalissimo' of the country during the war against Japanese invasion (1937-45); and lastly as head of the KMT government ruling Taiwan (1949-1975).

......

Two woodcuts are made to wrap up this centenary series: “Waiting” (No. 34) and “The Arab Spring” (No. 35). As things and events related to these two pieces are so fresh, there is no need to explain everything in detail.All inscriptions are of remarkable origins. I hope they can stimulate thought and contemplation. After working on these pieces, I became fond of Solveig's Song and jasmine.

There are some short stories I should like to recount before ending my catalogue notes

Over the past year, while I have been working on this project, a question has been frequently put to me. The question is: “How did the project come about?” The answer is: “It all started with a casual chat some time early last year (2010) among friends, most of them old acquaintances going back to my university years.” Over tea or wine, one of them exclaimed: “Now that it's the year 2010, the next will be 2011. A hundred years have gone by and things are still like this!” There was no need for further explanation; we all knew what he meant to say. The casual talk then turned into a preliminary exchange of ideas about my plan to produce a painting and woodcut series to mark the centenary of the Xinhai Revolution. Some of the friends joining the casual talk later became the members of my Xinhai task group.

The conclusion of our casual talk on that day was a straightfoward one, as offered by one of the participants citing the words of Sun Yat-sen: “The revolution has not been successfully concluded yet; comrades should strive on!” I later carved a seal based on this well-known saying by Sun, but leaving out the words “revolution” and “comrades”. The seal print now appears in some of the brush-and-ink paintings in this centenary series.

Another short story is my fond memory of my old mentor when I was a small boy living in Gaungzhou. His name is He Xia. I met him by chance at the age of ten, while I was making a sketch of a painting in an art gallery. He was then a retired old man of about seventy. He introduced me to the art of the Lingnan masters, in particular that of the founder of the School, Gao Jianfu. He later introduced me to another Lingnan master, Professor Chao Shao-ang, who would became my painting teacher when I moved to Hong Kong. Professor Chao had been the student of Gao Jianfu's younger brother Gao Qifeng, another famous Lingnan master. I know very little about my old mentor He Xia, except that he had been a soldier working at the side of Sun Yat-sen when he was young. He did not paint; he practiced calligraphy. He showed me his collection of calligraphy and paintings. I remember that a piece of calligraphy hanging in his study was penned by Sun Yat-sen. Some time last year, while digging out some old stuff in my studio, I found by chance that I still kept a letter written to me by my old mentor some 45 years ago. It was years after I moved to Hong Kong that I came to know the extraordinary life story of Gao Jianfu (1879-1951). He happened to be a member of the Revolutionary Alliance when he stayed in Japan in 1906. In the 1911 Canton (Guangzhou) uprising in April, he was one of the team leaders of the enlisted revolutionary fighters. He took refuge in Hong Kong after that failed attempt and continued to be an activist. After the Xinhai Revolution, he became a modern master promoting the 'New Chinese Painting Movement' and founded the Lingnan School. I very much share his guiding principle of 'New Chinese Painting': “brush and ink should follow [the development of] time.”

(Contents of the exhibition catalogue include: colour plates of all 35 artworks; chronology; an essay by Louie Kin-sheun; biographical sketches of over 50 historical figures; Fong So's catalogue notes and selected bibliogrphy.)

沒有留言:

張貼留言